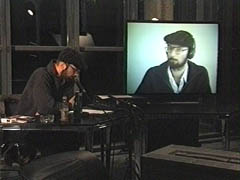

The "Dialogue" was performed at the opening ceremony of the new ZKM building, in November, 1997.

Tamás Walicky: V-R DIALOGUE

"V"= The "Virtual" Tamás Waliczky appearing on the TV screen (having been video recorded).

"R"= Tamás Waliczky in real life.

V: Welcome everybody present here today. I am Tamás Waliczky, and I am going to be leading a conversation with myself in your presence here tonight.

R: I 've been producing computer art for over ten years. The thoughts you are going to hear in this dialogue are the reflections of a media-artist.

V: I have noticed that whenever I attempt to express ideas of general concern, they will mostly be telltales of myself. The sentences starting: "People ..." or "Most people..." could in fact begin with "I ...". Therefore, I will now endeavour to speak about the personal artistic issue on a personal note, hoping that I will thereby speak "in generalities".

R: Tonight's conversation is going to focus on the following theme: In the past two years I have been facing many increasing doubts and reservations with regard to computer art.

V: At present, however, I could not imagine any more exciting, more up-to-date or more important type of visual art than computer art, itself. Naturally, that is also a matter of taste. For me this is the artistic form which is a challenge. I can very well imagine, however, that for someone else painting could have the same significance, moreover I can also very well accept that nowadays painting might well mean the greatest challenge. Nevertheless, for me producing pictures - paintings, graphics, photographs - has lost that versatile - magic, sacred, entertaining, educational - function which, I think, had originally called that type of activity into being. Of course, there are magical or entertaining pictures, perhaps even some sacred ones, but separately. For a contemporary viewer a Giotto fresco offered various types of experiences: an illusionary experience (the fact that non-existent things appear on the wall), sensual experiences (bright colours), the sense of wealth and power (suggested by the gilding and the awareness that it must have cost a lot), a sacred experience (the visual presentation of saints' lives and of holy stories), an artistic experience (the beauty of the forms, the rhythm of colours), the acquisition of knowledge (the visual presentation of biblical stories to a mainly illiterate audience). And all that on the highest technical and scientific level of the age. This complexity is of vital importance to me, and that is what I seem to find - perhaps naively - in computer art.

R: It does in fact sound a little naive, since it gives off the impression to me that computers are not only not richer, but much poorer and more primitive in their tools than all other picture-producing methods, so far.

V: One cannot preserve everything all at once. One has to lose certain things, for other things (which one previously regarded as more important ) will displace, repress them. Truly, through computer production the immediate freedom and richness of formulation will be lost. However, I will in exchange acquire limitations that are extremely inspiring, at least for me. I have never thought that the potentials of a computer might be unlimited. The limitations of the machine have always been more important to me, than its potentials. When I paint or draw a line, the way from the idea to its realization is natural and direct. If I do the same with a computer, I will first have to write a piece of software, or select an already exísting one, I will have to mark or enter the main parameters of the line. The whole procedure is very much like doing a crossword puzzle. Obviously, there are people for whom these limitations are rather disheartening. For me, however, they present a tremendous challenge: how can I realize my thought with such a limited, what is more, a primitive tool?

R: I am not only speaking about the technical difficulties of the production of a work of art, but also about the technically low quality of the end-product . If I look through the history of fine arts from a technical point of view, I can see that, for instance, in the case of cave paintings, pictures have no boundaries and neither is the technology of picture-production limited. What I mean by this is that since it is natural surfaces that are filled with forms, the artist's composition space is not limited. (They were not hindered in painting in all directions, to the right or to the left, upwards or downwards.) And also, since they used natural materials, their palette was not determined by the artist or by his technique, or at least that palette was open. Therefore, since it was very primitive, its possibilities were endless. The Egyptian pictographs displayed a much higher quality technique, so its potentials were also much more limited. The spacial boundaries were already manmade (although still remarkably huge) wall surfaces,and the colours, due to the refined technology, shrink onto the scale of a very small palette. Renaissance frescos are concentrated onto an even smaller area, and one has to walk much smaller distances in order to be able to view a picture. It is enough for one to stop in a well measured distance from the painting. Although the colours are bright and various, technology and experiential knowledge have formed a system of colours, which we until today have not much deterred from: some minerals and crystals considered reliable constitute the basic colours, the palette of which is of a very similar sort in all painters' workshops, and it is (by mixing these basic colours) that the shades of colours are developed. The traditional painting uses nothing but a relatively large rectangular or oval surface, and the observer stands in all instances, at one and the same point, when observing the picture. But even the smallest painting has an incomparably larger surface (that is to say its resolution is bigger) than that of a photograph. Furthermore, there is only a difference of about 7 F-stops between the darkest and lightest points of the photograph, which means that a photograph is much poorer in tones than a painting. This is, however, still a picture with an extremely high resolution, richness of colours and tones compared to the resolution in video technology. But, since video technology is an analogue system, within the very narrow boundaries the number of transitions is theoretically still endless, while the computer already limits the number of transitions and states foe example that in a given space the possible number of points positioned horizontally is 640 and those positioned vertically are 480, with precisely 64000 colours. This, of course, might seem a lot, but compared to the endless it is extremely few. Therefore, as technology is becoming more and more refined, picture-production is getting more and more primitive, and the most apparent example of this declinee is the computer.

V: This is only one possible interpretation of technological development. The whole process can also be understood as a transition from the analogue to the digital. It appears that analogue technology is no longer capable of development, whereas digital technology is radically new, being at the very starting point of its development. Already today there is cheap software that can manipulate images possessing a quality (similar degree of resolution, richness of colours and tones) close to that of photos, just a few years after the birth of computers. Anticipated by the present state of our knowledge there will be no obstacle to manufacturing computer screens of a million times million resolution and computers that are capable of computing such immense amounts of data. Much more important than this is, however, that the concepts (richness of colours, resolution, etc.) have only relevance with regard to computer art, as long as computer art wishes to imitate modern traditional fine arts. Since, even when reproducing a three dimensional model on the computer, the resolution will become unmeasurable: the resolution of the given computer screen is only the resolution of one window, through which we can look out onto a three dimensional, nearly unlimited virtual world. In the case of Virtual Reality or Cyberspace we can speak about virtually endless worlds, and in these spaces forms are positioned in a way similar to the chance manner as of cave paintings. This is truly a new complexity, and I hope that computer art is capable of meeting the various functions that provided the enviable variety of traditional arts.

R: The various functions of the work of art are relevant for one reason only: with regard to the relationship between the work and its audience, the work of art and its contemporary age. In other words: all this complexity plays a role in the communication between the work of art and its audience. I, however, do not think that the main point of arts is communication. On the one hand, I do not believe that the artist makes his work for his audience (for me, audience is rather a necessary evil: dodging, avoiding their expectations, as obstacles may force me to perform efforts). On the other hand, I do not believe that the audience is captured by the information gained from the work of art. If, however, it is not the audience that I produce my work for, then for whom? Perhaps I work for myself. But I am sure it is not true, it would be a kind of folly, which is far from what I consider artistic work. Working for myself or for others: this sounds like an atheist viewpoint, which knows no other variables. Ancient Greeks define the causes of human activities in a much more refined way, by describing all activities with THREE variables - with the individual decision, the compelling force of the environment (the other people), and the active partaking of the everywhere present Gods in events. So as to be able to answer the question of who I am producing my work for, I would also like to introduce the notion of the transcendent. The way I see it: God is still existent, though might be hard to find. The possibility, however, is still there: each person can find one of God's faces. Artists are the ones who, in a fortunate case not only find God's face they are meant to find, but also inform others about it in their works. This way, then, all works of art are `Gospels', the Good News, since they prove that something very important is still there, still has not gone totally missing. Artistic work for me is, therefore, the search for God's presence, so it is rather isolated, not bound by current matters, independent of the response of the audience. A work of art radiates the joy derived from the finding, through which it grips the audience, and is, thus, timeless. The changes in the world may cover it temporarily, may even destroy it, but it will reemerge again and again. This, however, means that even the smallest painting, not known to any one person, might well mark a much more important event, than a popular, high budget electronical work of art, applying the highest level contemporary technology. For me, then, the question whether one can produce a sacred work on the computer or not is much more significant, than its versatile ability of processing and communicating data.

V: If we are to accept that all good works of art are - at least partially - sacred, then the question is to be the following: is it possible to produce a work of art on the computer? One of the most important components of arts for me is the freedom it possesses, that it can emerge at the most unexpected places and can resist categorization. For instance, as soon as it has been declared that fine arts is defined as works of art displayed in galleries, graffiti turn up on walls, and sooner or later they, too, get integrated (and are purchased) under the term 'fine arts', etc. There is a kind of circulation: artists attempt to show what is lively, unclassifiable, unique, and thereby become excluded from the received norm. In a while, the norm itself becomes altered, as well, and embraces the works of art that were not digestible just yesterday, yet. I suspect that the use of the computer as a medium in fine arts is such an unexpected, hardly digestible leap for outsiders and a search for a novel lively form for artists, or at least originally must have been. When I produced my first computer work in 1986, it was vital to me that the galery staff would not be able to process what I was doing. This was very important in the Hungary of the times. I did not need a permission for taking my work abroad when I wanted to take them to an exhibition outside the country on a floppy disc . I did not need an arts degree. So, this way, having dodged the not at all art-friendly art bureaucracy, and having taken use of the growing interest for the new medium, I could show my works to the audience, could receive their feedback, and last but not least I had success. At that time the computer did not seem counter-artistic to me, at all. What is more, it offered me the opportunity to build my own art in a relaxed manner, with an enthusiasm for the potentials of the new tool. The computer meant a TOOL to me, without which I wouldn't have been able to develop my ideas . I would then say: "the computer does not, by any way, alter 'man', the determining unit of our world. With the help of the computer, we can yet have another look at the forever valid theme, except perhaps from a little different camera position." In other words I thought I was producing traditional art, but with a new tool, and of course in a new visual form, due to the new potentials of the new tool. But that was what happened when photography or the movie camera were invented, or when the video appeared. I do not understand why we should be alarmed when the computer appears on the scene. The computer is a logical consequence of video technology, of movies and photography (of course, seen only from a visual point of view). Which means that it faithfully mirrors our present-day culture and the direction we have taken. We would not have invented it, had we not needed it. It would be hypocritical to say that the computer is counter-artistíc, but video is not, only because video technology had been there for some years, and have become an integrated part of our lives. Of course, I could say that mankind is following the wrong path (and I would probably be right), but would it help much to try to erase the last couple of years from the history of technological development?

R: I would like to answer these ideas one after the other. I think, that discovering the new potentials of the new medium causes over-enthusiasm of course, and over-enthusiasm certainly takes hold of a person. Around 1990 I felt that I all of a sudden became one of the circle of artists, who were producing a very interesting new artistic form. Moreover, I could feel that I was a pioneer in that field in Eastern Europe. So, I could be flattered by thinking that I was more important than I actually was. In this frame of mind it was easy to persuade myself to avoid thinking through certain things, or not to answer certain unpleasant questíons, since the common "cause" seemed more important than small details. I, for instance, did not notice, or did not want to notice that while traditional art exhibitions - good or poor - should have art in their focus, computer art exhibitions, festivals had all type of other things in the centre (e.g. technology), except art itself. I think that there is one vital difference between the computer and other tools discovered by man so far. So it is worth NOW contemplating which direction to follow. I will try to formulate the difference in my own way, apologizing for the unscientific manner of my words in advance. So, the way I see it, there are TOOLS that man invented to extend the opportunities the human body offers. The paint-brush, the knife, the saw, the hammer, the drill are all various types of the extension of my hand. Similarly, a pair of glasses, the magnifier glass, the microscope, the binoculars are the extensions of my eyes. Then there are some MACHINES which not only support the capacities of certain parts of my body, but are capable of mechanically modelling certain abstract human ideas. For example, a drill can intensify the power I can produce, making a hole in a relatively soft material. The drill machine realizes the idea of "drilling", that is the rotating movement, the pressing energy, etc. The camera realizes a particular type of seeing, and should there ever be a real-time 3D scanner, that will mechanically realize another type of idea of seeing. The train and the car model the idea of movement, the aeroplane and the helicopter that of flying, which shows that ideas that are the basis for the manufacturing of machines do not only include capacities of the human body, but also human dreams. And finally there are the THINKING MACHINES, which are meant to model the idea of "thinking". (In brackets : it is to my particular joy that as there has never been one instrument or machine that could have precisely modelled a human part of the body or a feature, these thinking machines will not either be able to precisely model thinking.) And as man himself - rightfully or not - finds the capacity of thinking very important and distinctive, I, too, feel it justified to draw a very strong boundary between machines and THINKING MACHINES.

V: Let us presume that there is a doctor who operates on ill people out of vocation. Let us presume that this doctor would honestly like to help. First, he uses a knife, then as he can afford it, he goes on to using more expensive instruments, a microscope and such, which make his work more secure and easier. Finally, he hears that a new computer controlled laser instrument has been developed which would perfectly fit his purposes. Why should he not use that new instrument? Since he has his aim clearly set, why should he confuse himself by agonizing about the nature of the machine he uses? If my task is clear and obvious, I will be using my instruments and not the other way round, me being a slave to them.

R: My job, as an artist, is not that clear and obvious. It cannot even be, due to the nature of art. A doctor has vowed to eliminate or at least lessen suffering, and to serve that with all kinds of means. Their job is respectable and useful. But my artistic work is surely not useful, or at least not in such a rational way, and while producing the work of art, I cannot at all see my purpose so clearly. What I find is often surprising even for myself. My job connects much more to the abstract, instead of knowledge; to intuition, instead of light to the mysterious. And in this sometimes slow, fumbling process, in the course of my work, which is sometimes a sudden, surprising discovery even for me, sometimes despairingly insecure, the material and tool I am using may be of immense help, due to their nature, resistance and sobriety. (For example, in the case of painting, it is surely the paint and the canvas that do half of the work: one must let them work , too.) This is why I think that in my artistic work, I have to be very careful about choosing the tool and material I am using, since they will, too, have an effect on the whole of my work, but may even change me. I once read in a Chinese aesthetical writing how an artist answered a question: "What else could have called my work into existence than the blending of my own spirit with that of the wood (I was using)?" This, thereby, makes me a little concerned what sort of cyborg-art will be produced by the blending of my spirit with that of the computer's? Besides, I am not even certain that suffering should be avoided. No question about it, CAUSING suffering is sinful, but it might be just as sinful to try and run away from my own suffering. This is a very difficult question, since perhaps all human inventions were made with the intention of either causing or eliminating suffering. The first half of the question is easy to understand, remembering the great variety of all the destructive, murderous weapons.The second half of the question is perhaps more difficult to grasp, so I will try to explain it through an example. I have a Swedish friend, who was born physically disabled. He could not coordinate his movement, could not walk or get dressed alone, could not eat, his speech was hardly comprehensible. The Swedish welfare state surrounded him with immense caring all throughout his life: a nurse looked after him. Later on, based on his own plans, he had a special device made for him that could feed him, comb him, button his clothes. He arrived in Hungary in a Saab car which he could control with his feet and the with the movement of his head. He came to Hungary to visit the Pethõ Institute, where such physically disabled people - mainly children - are treated in therapy. At Pethõ Institute he was advised not to use his special devices, but try to learn how to control his own body. First he thought this was impossible, since he had been told in Sweden all his life that he would never be able to eat or dress alone. This, however, did not cause him any difficulty, since the Swedish society accepted him as he was, and the various devices helped him meet his needs for movement, eating, etc. Nevertheless, he undertook to attend that treatment for a few months at Pethõ Institute. Here, step by step, with the help of various exercises, he slowly learnt how to lift his hands to his mouth, or keep his legs straight. These exercises were very often extremely painful, and since he did not, for a long time, believe that these exercises could have a good effect, he needed immense will power to do them again and again. In other words: he took on a tremendous suffering, at first without any hope. After a while, however, he was able to lift the spoon to his mouth. From then on he started a life in Budapest that he had not had a chance for ever before: without aids or devices, totally on his own. He forced himself to get dressed, wash and eat by himself. Soon he achieved that he was able to take care of himself just as well as anybody else. At the same time immense anger took hold of him. He felt that in Sweden, the tolerance and caring he had received, deprived him of being able to get to know his own body, to become an independent person. He returned to Sweden and started giving talks about his experiences, which resulted in a huge scandal. He was accused of lying. People tried to prove that he had been able to walk already before his trip to Hungary. At present he is doing his best to establish a Pethõ Institute in Sweden. I would like to make it absolutely clear that it is not my intention now to speak about the difference between Sweden and Hungary, between East and West. The Pethõ Institute is also an isolated case in Hungary. A large number of Hungarian doctors are of the same opinion as their Swedish colleagues. For me this story clearly demonstrates that while Swedish doctors were absolutely benevolently convinced that suffering should be eliminated, my Swedish friend, decided to accept suffering with a strong believe in its saving power. My Swedish friend felt deceived, because he felt that instead of having a chance to live a real life where he himself would be able to control his own body, he was directed to live an artificial, a fake life. Suffering and problems cannot be erased: one has to refund them with the reality of one's life. The same way as my Swedish friend - instead of trying to control his body - was wrecking his mind about devising a machine that would feed him, comb him and button his dress, does a scientist proceed, who instead of solving the problems of reality, wrecks his brain about devices that would create virtual reality devoid of any problems, or uses machines made to solve real problems for creating such virtual reality. It is, then, questionable whether I will be able to produce a real work of art about real problems using the virtual tools of a virtual reality, enjoying the virtual success gained from the virtual responses of the audience, when I, as an artist, try to use the technology of Virtual Reality as a tool for producing my work of art .

V: I hope that even in this case I will be able to make a real work of art about real problems. But am I real, now in that screen? Am I talking about real problems with myself, or about virtual ones? I would, however, prefer to leave these questions unanswered for the moment. Perhaps this is my way of creation: to make art pieces from my deep doubts.

Copyright © T. Waliczky, A. Szepesi, 1997

Translated by Emõke Greschik, Tamás Waliczky and Anna Szepesi

Pictures recorded by Jan Gerigk